We have the act itself (the sinking of a ship), as well as the end to be gained (keep the British government in power and torpedo a peace initiative) and the circumstances surrounding it (an attack outside the exclusion zone in an undeclared war).

The History of the south Atlantic conflict The War for the Malvinas Ruben Moro 1989, p.165.

The ARA General Belgrano was an Argentine Navy cruiser which was controversially sunk by a British submarine during the 1982 Falklands War as she sailed away from the conflict zone. 323 people died, mainly young sea cadets.

Originally a US Navy cruiser, launched in 1938, the ship survived the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and was decommissioned from the US Navy in 1946. In 1951, the ship was sold to Argentina. In 1956, the ship was renamed ARA General Belgrano after a hero of the Argentine war of independence.

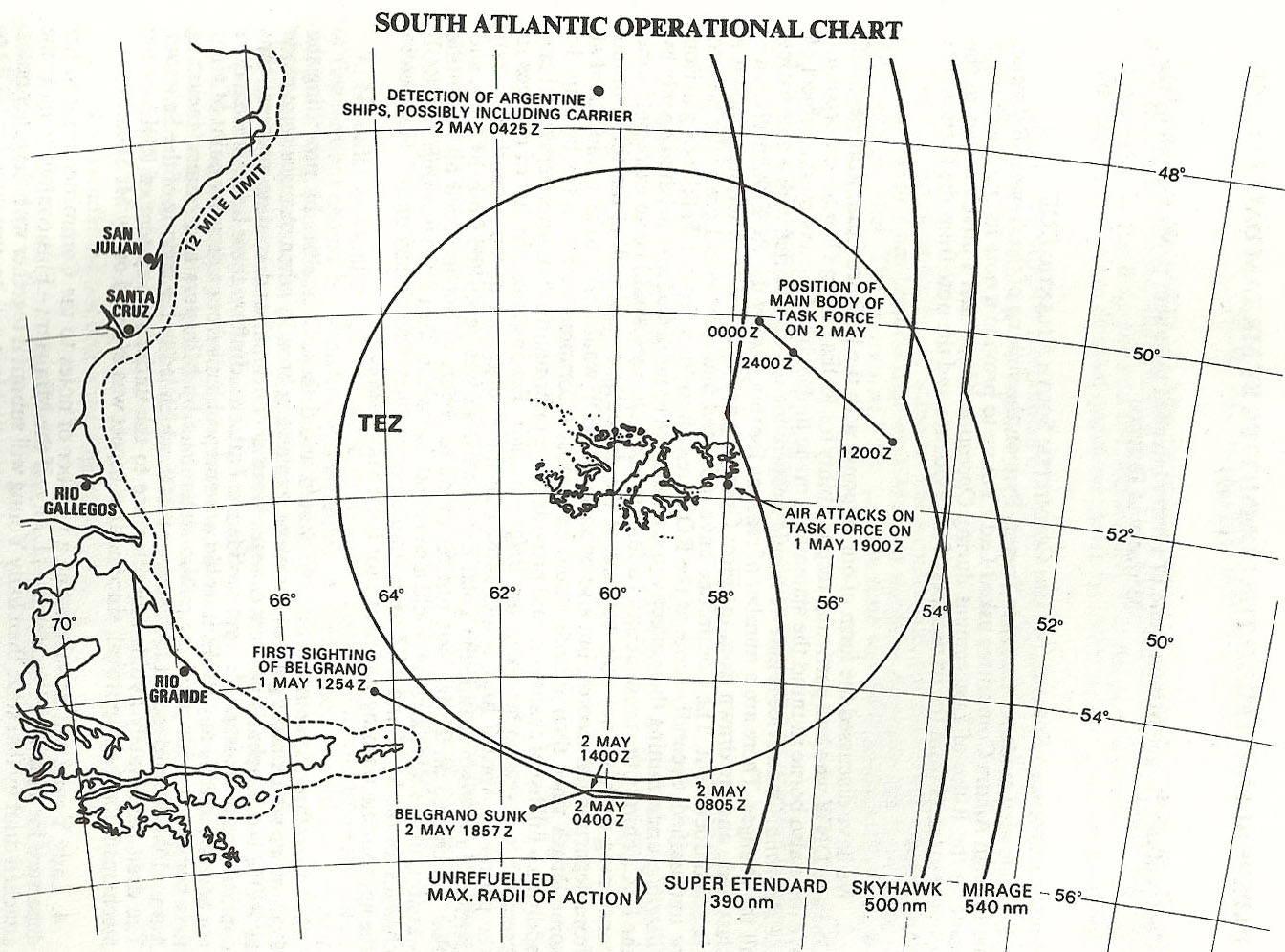

On April 26th, 1982, the General Belgrano, accompanied by two destroyers, left the port of Ushuaia in southern Argentina. On April 29th, the Argentine task group began patrolling South of the Falkland Islands. On the following day, the ship was detected by the British nuclear submarine HMS Conqueror which gradually closed over the next day. On May 2nd, HMS Conqueror fired three Mk 8 mod 4 torpedoes, two of which hit the Belgrano.

With the ship holed, no electrical power, and unable to pump out water, the Belgrano soon began to list to port and sink towards the bow. Captain Hector Bonzo therefore ordered the crew to abandon ship using the seventy-odd rubber dingys.

Tragically, the Belgrano’s two escorts did not know that something had happened to the Belgrano and continued on a westward course. By the time that the escorts realized something had happened to the Belgrano, it was already dark, the weather had worsened, and the Belgrano’s life rafts had been scattered.

Consequently, even though Argentine and Chilean ships did rescue 770 men over the next two days, 321 members of the Belgrano’s crew died. In early editions on Tuesday May 4th, 1982, Britain’s The Sun newspaper led with the infamous headline “GOTCHA”: “Our lads sink gunboat and hole cruiser”. When news began to emerge that the Belgrano had indeed been sunk, with a large number of casualties, later editions of the Sun led with the more sombre headline “Did 1,200 Argies drown?”

Consequently, even though Argentine and Chilean ships did rescue 770 men over the next two days, 321 members of the Belgrano’s crew died. In early editions on Tuesday May 4th, 1982, Britain’s The Sun newspaper led with the infamous headline “GOTCHA”: “Our lads sink gunboat and hole cruiser”. When news began to emerge that the Belgrano had indeed been sunk, with a large number of casualties, later editions of the Sun led with the more sombre headline “Did 1,200 Argies drown?”

THE CONTROVERSY

The sinking of the Belgrano became a cause célèbre for anti-war campaigners in Britain. This was for a variety of reasons, including the ship being well outside the 200 mile (320 kilometre) Total Exclusion Zone that the British had declared around the Falklands, because the ship was on a westerly heading at the time it was attacked, and because a Peruvian peace proposal was still on the table at the time of the attack.

Was the sinking of the Belgrano justifiable under international law?

Some argue that, the ship being outside the British-declared Total Exclusion Zone would not affect this analysis, since the British Government stated on April 23rd, that ‘the approach’ of any warship or aircraft ‘which could amount to a threat to interfere with the mission of the British forces in the South Atlantic’ would encounter an ‘appropriate’ response. The Belgrano was neither ‘approaching’ the task force and was it a ‘threat’? That statement was put out while the British task force was still travelling South, as a warning that any approaching aircraft etc might be shot. Once the Task Force had arrived, it then announced on 28 April the Total Exclusion Zone – and, that would have superceded an earlier statement. War was not declared, that is why these definitions were important.

Some Argentine Views

on May 3rd 1982, Argentina’s Foreign Ministry released a statement, that the sinking of the Belgrano was “at a point at the 55 º 24 ‘south latitude and 61 º 32′ west longitude. That this point is located 36 miles outside the area maritime exclusion set by the government of Great Britain. Such an attack is a treacherous act of armed aggression.’

Was it? Debate has raged on this issue, mostly misinformed due to the torrent of British MOD fabrications. This website will enable you to have that calm debate you always wanted to, but based on correct info.

Let’s hear a statement by Alicia Pierini, Ombudsman of the City of Buenos Aires on April 25 2005:

“The Argentine ship was away from the area of belligerency, not navigating towards it and not even close to any British units: so it could not have been any threat or danger to the United Kingdom. Torpedoing it was, quite simply, a war crime, through the disproportionate and illegitimate use of force in violation of the rights of those who fought then. Why would Britain have designated the exclusion zone – thus drawing the boundaries of war-theater – if it was immediately to be violated? “

Political analyst Rosendo Fraga expressed the following cautious view, immediately prior to Lawrence Freedman’s Official History appearing in 2005:

The debate over whether the British attack took place within the international rules to be respected in conflict or outside, is controversial. Probably resolving the issue will be the function of legal historians, politicians and diplomats. The reality is that the cruiser was sunk by breaking rules, but the international community seems to have taken over the matter, not mostly sharing this view. For Argentines, the idea that the cruiser was sunk in violation of the rules will remain as a manifestation of the Argentine claim to sovereignty, though the world does not share this view and only historians can give a more definitive opinion about it.

Vice Admiral Juan Jose Lombardo, in an interview published in the NATION March 31, 2001 said this:

“I gave the order to attack on 1 May. When the British force set out to land would be the key moment of danger and their whole strategy would be to defend people who disembarked. Then they put all their elements, including submarines, to defend that position. That was the moment when we had to take the opportunity to do something. It was time to think about a transport strike, a damaged ship [?]. But, three groups of attack open to the West to wrap and search vessels were lost [?]. Six hours, after I send a new message to Allara (the head of the fleet of sea) landing there, that because of serious danger to their ships, they should retire? “

Six hours after the abortive Argenine attempt to attack, on May 1st, he gave the order to retire. That is important as a statement by the man who was the Commander-in-Chief of the Argentine South Atlantic Theatre of Operations.

In 1994, Argentina added its claim to the islands to the Argentine constitution, stating that this claim must be pursued in a manner “respectful of the way of life of their inhabitants and according to the principles of international law.” It would be strange if also in 1994 the Argentine government conceded that the sinking of the Belgrano had been a “legal act of war?” The evidence heard at the Belgrano Inquiry – here summarised – offers an alternative view. You decide.

It would have been a legal act of war if the Belgrano had either the intention or the capability to threaten Britain’s Task Force. Did it? That depends upon what its mission was. Arguments of ‘military necessity’ for sinking have a logistical problem: had it been perceived as a threat to the Task Force, that would have happened on May 1st, while it was sailing East, towards the Task Force. That didn’t happen. Only after it had turned round and had been sailing East, for 11 hours, away from the fleet, was it sunk.

That’s what it was doing.

Cartoon by Steve Bell

Well if you cannot stand a bloody nose then do not start a war with a determined enemy.

I’d be interested to hear of any precedent for this as a war crime, a crime against peace possibly (though that would still be a stretch) but I’m pushed to see how how this can be construed as a war crime except where a political agenda to have it so exists.

In any other conflict (dabbling in whether a formal declaration was given is counting angels – territory had been militarily violated) active, regular naval units engaging each other wouldn’t be given a second thought. Which brings us back to the exclusion zone, which the Argentine govt were explicitly informed was announced as “not by way of limitation”, as indeed such arrangements traditionally are – Hector Bonzo seems happy enough that he & his hands were a legitimate target, why should we think different?

This ‘controversy’ is nothing of the kind, and the ‘Argentine view’ put forward here is not actually the view of any qualified Argentian official. Argentina’s own government, its navy, the admiral commanding the Argentine fleet during the war, and Hector Bonzo, the Belgrano’s commanding officer, ALL concede that the sinking of the Belgrano was a legitimate act of war, a war that began with an unprovoked Argentinian invasion of the Falklands.

The mere fact that the Belgrano had turned back after its attack was cancelled is immaterial – it was a powerful warship capable of inflicting severe damage on the British fleet had it been allowed to come within striking distance. As the above post concedes, the ship was on war patrol, and would have sailed back and forth – it was not headed back to port and was not ‘no longer a threat’ since it would have been ordered back on the attack had the opportunity presented itself. The initial attack was not cancelled because of any pacific intent by the Argentines – whose attempted aggression during what we are supposed to believe were genuine attempts to make peace this site totally glosses over – but merely for tactical reasons, and was awaiting a better chance to attack.

The sinking of the Belgrano remains a ‘controversy’ only to those who have simply been unable to let go of their hatred of the United Kingdom and/or Margaret Thatcher. This website does not offer an ‘alternative view’, instead it attempts to continue a dispute that has already been settled using the statement of a minor city official (the Buenos Aires city ombudsman), a failed law suit (the 1994 case was dismissed in the European courts), and the statement of an analyst who is neither an expert in military, nor history, nor legal affairs. Quite simply, it attempts a fraud on its readers.

The illogicallity of this website’s position is easily demonstrated: throughout the conflict Argentine jets flew over the islands, dropped bombs on the British fleet, and then returned to their bases. Also throughout the war the British attempted to shoot them down, preferably on their way in, but also on their way out since they would inevitably return with more bombs if they were allowed to escape. Yet, according to the ‘logic’ applied here, it would have been a war crime and an act of aggression to shoot them down on their return trip despite the fact that they were sent back out on the attack after arriving back at base, because once their attack mission was over, they were, according to this site’s author’s reasoning, no longer a threat.

I have no argument with the fact that the sinking of the Belgrano was a terrible thing that should have been avoided – but the best way to have avoided it was by not starting the war in the first place. Whilst the British government of the time, and its predecessors, deserve a small portion of the blame for failing to properly deter an Argentine attack, and for failing to take the threat of war seriously, the decision to invade the islands using military force was made by the Argentine Junta. After this decision was made, baring any genuine meaningful offer of peace involving a return to the status quo, which the Junta had ruled out, the lives of any Argentine servicemen serving in the Falklands in a capacity that threatened the British fleet were subject to the fortunes of war. This included the Belgrano and her crew.

In attempting to make this sinking primarily the fault of the British government, this website is attempting to perpetrate a despicable fraud on its readers. The authors should be ashamed of themselves.

To FOARP:

Argentinian jets were legal targets (in their way back home) because they entered the exclusion zone, and bombed or tried to bomb (which they did many times and succesfully), british ships. Belgrano was OUTSIDE the exclusion zone, and going back. With your criteria the british task force could have shelled/bombed continental bases, or Buenos Aires itself because they where potential threats?? Cmon! Your point is as one sided as the one you are pretending to deny.

As an ex combat pilot of the argentinian air forceI I tell you this… I find more logic in Andrew’s answer.

Alejandro – I see your point, yet the Argentine military plotted an attack on British forces in Gibraltar, did they not? Much as the British also attempted an attack on Rio Gallegos?

By the point we are talking about, British forces had already fought a battle with Argentine forces in South Georgia – outside the exclusion zone – in which they had depth-charged and captured a submarine (the ARA Santa Fe). The first ship sunk during the war might well have been that submarine – with acompanying loss of life – had it not surrendered first.

Personally I think talk of the exclusion zone is somewhat vacuous – by the point we are talking about, action was not, anyway, restricted to inside the exclusion zone. Hector Bonzo said he was well aware of that, as did Admiral Allara. Admiral Molina Pico said that they were preparing an attack. All these men seem well qualified to speak to the matter, so you need not need simply trust me on it.