Lawrence Freedman was knighted by Prime Minister Tony Blair,[1] and then requested by Blair to compose his two-volume Official History of the Falklands Campaign. His account has endorsed the standard view of the Thatcher government, that the sinking of the Belgrano and the failure of Peru’s peace initiative were two parallel but unconnected events, over the weekend of 1-2 May, 1982. Where it differs from the historical Thatcher government line, is in its fabrication of an absurd new claim about instructions sent to the Belgrano.

The story coming out from our 1985 Belgrano Enquiry had been, that in the early morning of 2nd May 1982 the Argentine fleet turned round and headed for home because of the developing Peruvian peace plan, which the Argentine General Galtieri was accepting. The Belgrano was sunk that afternoon at the last possible moment when Britain could still deny having knowledge of that plan. The ship’s crew were in no way expecting such an attack, because they were well outside the 200-mile radius Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) and were heading away from it, having been on patrol south of this; they were mostly in the ship’s restaurant or in their bedrooms when struck. A nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine fired three torpedoes, two of which hit the Belgrano and one a neighbouring escort ship.

The story coming out from our 1985 Belgrano Enquiry had been, that in the early morning of 2nd May 1982 the Argentine fleet turned round and headed for home because of the developing Peruvian peace plan, which the Argentine General Galtieri was accepting. The Belgrano was sunk that afternoon at the last possible moment when Britain could still deny having knowledge of that plan. The ship’s crew were in no way expecting such an attack, because they were well outside the 200-mile radius Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) and were heading away from it, having been on patrol south of this; they were mostly in the ship’s restaurant or in their bedrooms when struck. A nuclear-powered hunter-killer submarine fired three torpedoes, two of which hit the Belgrano and one a neighbouring escort ship.

A real, fierce killing war broke out once the Belgrano had been sunk, because that act scuppered the peace negotiations. British ships were sunk, many lives were lost. It’s important to remember that Britain was not at war until that act: Pym the foreign Secretary was in Washington urgently negotiating with al Haig to try and pull out a peace deal. Pym told journalists on his arrival in Washington (May 1st) that the day’s military activity – the British attack upon Port Stanley – was to ‘concentrate Argentinian minds’ on the need for a peaceful settlement, and he added, ‘No further military action is envisaged for the moment other than making the total Exclusion Zone secure.’ The TEZ had been announced on the 28th April, and Britain’s Foreign Secretary spoke on May 1st about making it ‘secure’. The whole Task Force expedition was done under Resolution 502 of the United Nations Security Council, which implied a minimal use of force.

Lawrence Freedman’s account seems not to accept that the Argentine fleet had thus turned around in that midnight 1-2 May,[2] or in any way accept that the urgent peace negotiations being conducted nonstop over that weekend in Lima impacted upon anyone’s policy.[3] Let’s remind ourselves that Al Haig had his job on line here, he had put a lot of personal initiative into pulling out this peace deal, above and beyond the call of duty[4] – because the USA really did not want a war between two of its allies – and when it failed, Reagan sacked him. Also, Britain could not have conducted the war at all without US support, for refuelling on Ascension Isle and for satellite intelligence of fleet positions in the South Atlantic.[5] So, if for no other reason than US pressure, the UK had to go along with peace negotiations.

It’s a shame his Official History didn’t take on board Virginia Gamba’s view – after all she was his colleage in his visit to Argentina after the book was published, and she like him was a lecturer at the War Studies Department of King’s College London:

Attacks on the [British] fleet dwindled towards nightfall, and stopped when the fleet distanced itself from the islands and dispersed. The order to attack was reversed before 10.00 p.m on May 1, and the Argentinian ships fell back to hug the Argeninian coast, keeping well away from the British-imposed exclusion zone. Some units headed back to the coast, zigzagging to avoid detection by submarines.

In Buenos Aires, the decision-making apparatus was not marked by frenzy. The only action of the day was the formation of working groups to analyze whether Argentina should go back to the Security Council and refer to the new situation to demand an amplification of point 2 of Resolution 502. Negotiators would ask for mutual withdrawal, but expect a British veto. (The Falklands/Malvinas War, 1987, p.166.)

After May 2nd, the UK government responded to questions about why it had sunk the Belgrano with a nonstop barrage of lies, lies over every conceivable aspect of the situation. So much so, that Michael Heseltine the Defence Minister developed his ‘slippery slope’ position: he would not go on answering questions about the Belgrano, because this might only put him on a ‘slippery slope’ of disclosure which would risk ‘irreparable damage to our national security,’ i.e. the truth might come out. Our Belgrano Enquiry did scrutinize these untruths. I think it’s fair to say the British people did not respond with a great deal of interest, judging by the present Wiki site where very little is true: it merely reiterates the British Navy’s gung-ho position, now canonized in Sir Lawrence Freedman’s bulky opus.[6]

Argentine records, of when Argentine ministers ordered their ships to go where, or who phoned who when, are hard to come by, and forget about any Argentine newspapers for mid-March of 1982. But, there is a fine history book by Rueben Moro, A History of the South Atlantic Conflict 1989, with a new edition coming out that will grapple with Freedman’s claims.

Thus, the five-page review of Freedman’s book (in Political Studies Review, 2007, vol. 5) by Vincente Palermo does not hint at any Argentine documents whereby he could evaluate the truth or otherwise of the claims there made: he is simply believing everything in Freedman’s Official History – with other views marginalized as ‘conspiracy theories’. Freedman doesn’t refer to the book written by Belgrano Captain Hector Bonzo in 1991 ‘Tripulantes del Crucero ARA General Belgrano’ which he clearly should have done. Admittedly, it might have nullified his argument about its alleged plan of attack. I haven’t seen it either, which brings us back to the difficulty of obtaining Argentine sources.

The Peruvian government used to insist that it had a record of the vital phone calls and telegrams it had made over that key weekend, and that they would be released one day, and that they would show that the British knew what was going on[7] – which Thatcher’s government strenuously denied. It now seems unlikely that anyone will find these. The problem here was – as Tam Dalyell explained, after he visited Peru to find out – they would have to be requested by some official body, such as the British Labour party, who would not do that. President of Peru, Belaunde Terry, said to Tam: “I know that your government and your Prime minister knew exactly what I was doing,” adding, “One day there will be the documentary evidence.” (The Unecessary War 1986, p31) That now looks like undue optimism.

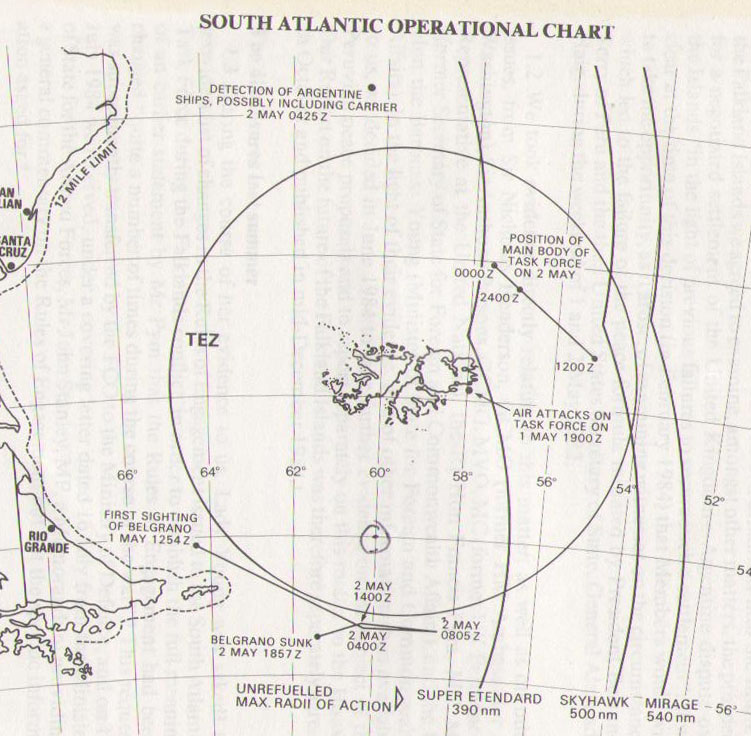

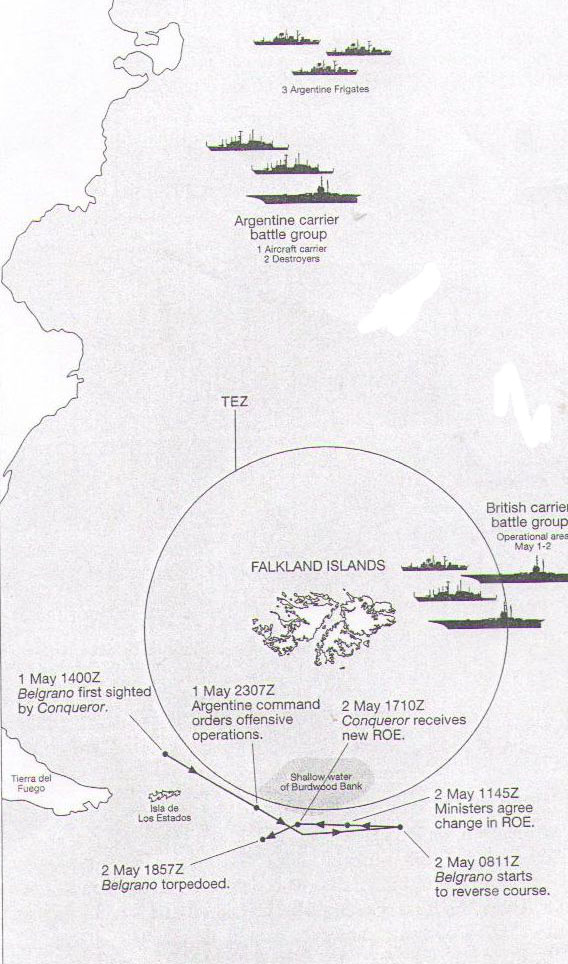

- Map shows the 200-mile Total Exclusion zone around the Falklands, plus the alleged position Freedman claims the Belgrano was ordered to head towards.

Most of the great experts who participated in our Belgrano Enquiry are now departed alas, and those still alive like Clive Ponting seem to be keeping their heads down. We, who strove hard to find out what really happened in the 1980s, have been sidelined as ‘conspiracy theorists’; by Freedman. Having said that, there is a central Untruth around which Freedman’s account revolves, and it’s such a whopper that we are startled anyone could allow it. To start with, we view the map of the Southern part of the TEZ (Total Exclusion Zone).

Added to the map are co-ordinates of that part of the south Atlantic where, according to Freedman, the Belgrano had been ordered to relocate, in order to prepare its attack upon the British task Force. Did GCHQ release this all-important information twenty years later, in order to help Freedman write his book? Such a disclosure would have been manna from heaven for Margaret Thatcher, delivering her at a stroke from the awkward questions being put by Ian Mikado, Tam Dalyell and the like. The Belgrano was her nightmare – she knew she had gone over to Northwoods on that fateful Sunday afternoon, and personally ensured that the command had gone forth, irrespective of any info about it changing direction and sailing constantly away from the task force. That ancient ship was then twenty times further away from the Task force than the maximum range of its guns.

A newspaper headline heralding Freedman’s forthcoming book proclaimed:

‘’Belgrano ordered to attack British ships on day before sinking, secret report reveals’

(Independent 28.12.03). The obvious question here is, if it’s been secret for twenty years, why should anyone believe it now? Can it be produced or shown in any way? Freedman had told a journalist: ‘The intercept confirms that the Belgrano was under orders to attack on May 1. It does nothing to confirm the contentions of Mr Dalyell, and broadly supports what was said by the Government at the time.’ No wonder Freedman was knighted! Once his smart leather-bound 1500 page two-volume book emerged, Dalyell and the Belgranauts (as Freedman calls us lot) were firmly marginalized as ‘conspiracy theorists.

On the evening of May 1st, the Vincente de Mayo aircraft carrier was way North of the TEZ, loaded up with fighter planes all set for battle. Their heavy load meant they could only get airborne on the ship’s runway if the wind blew, which it didn’t. How different the war would have been, had the planes been able to take off and fly about three hundred miles to attack the British Task Force! The British subs were trying to find the Vincente de Mayo because they had a specific instruction from the War Cabinet at Checquers to sink it – but, it was too far away, and so they hit the Belgrano instead. The former might have been a credible act of self-defence (but not in Pym’s view[8]), the latter act was always a war crime. For a short while the aircraft carrier and its escorts were indeed moving South-east towards the Task Force, during the night of 1-2 May, while this intent-to-attack command had gone forth, primarily from General Lombardo the supreme commander of the Argentine fleet, but also General Alloa who was on the Vincente de Mayo.

Here is the startling passage, whose validity we here question, in Freedman’s book:

The Belgrano group, TG 79.3, which was then to the north of the Exclusion Zone [no it wasn’t, NK] was to deploy South to Burdwood Bank, and then to close in on the British to deal with any surface units operating to the south of the Falklands. Within a few hours of this order being issued, this was being relayed to the Task Force as an intelligence summary: ‘It is believed that a major Argentine attack is planned for 2 May. BELGRANO is deploying to a position 54.00S 060.00W to attack targets of opportunity S of the Falklands Islands.’ (p.285)

Nothing remotely resembling such info was ever released, during the great debates on the topic in the 1980s. Nothing would have been more valuable to Margaret Thatcher on the subject which became her nightmare – how she precipitated that war whereby she became re-elected as the ‘Iron Lady.’ Ah, can you remember all the flags flying, as she put the ‘Great’ back into Britain?

Sir Lawrence Freedman should be obliged to answer the question, how come nothing resembling this alleged intercepted directive – on which his story hinges – was present in the so-called ‘Crown Jewels’ dossier which Clive Ponting was asked to prepare for the Defence Minister Michael Heseltine, later evaluated in Ponting’s book ‘The Right to Know’? That dossier had all of the high-security info surrounding the sinking. Any such message intercepted by GCHQ, would have had to have been there.

Quotes from Hector Bonzo

Here are some quotes from the captain of the Belgrano – not given in Freedman’s book, which show what the ship was doing:

1.Legitimacy: The sinking of the Belgrano had been “politically criminal”[9].

2. Heading home: He confirmed that his ship had indeed been ‘heading home’ due West, when hit (Ibid).

3. Was the Belgrano a ‘threat’ to the Task Force? “Absolute nonsense. The nearest British surface ship must have been 250 miles off. I’d have needed 14 hours to catch it at my top cruising speed of 18 knots, provided it stopped dead in its tracks. 3.6.83,(Gavshon & Rice, FAC Report 1985)

4. Outside the Exclusion Zone “One thing puzzles me. You Anglo-Saxons are supposed to be so logical. As a mere Latin, I thought that a Total Exclusion Zone must mean that if you were in it, then you get shot at. If you were not in it, you did not get shot at. But if you are going to be shot at in any case, why have a Total Exclusion Zone at all?” Captain Bonzo, of the Belgrano (Gavshon & Rice, The Sinking of the Belgrano, p.112).

5. A pincer movement? ‘It would have been an odd pincer movement, Bonzo said, with the prongs some 350 miles apart’ (Gavshon & Rice, p.111) If anything, the ‘carrier battle group’ with the Vincente de Mayo was more like 400 miles due North of the Belgrano. Freedman’s account keeps harping on this ‘pincer movement’ alleged threat, as being the ‘military necessity’ for it being sunk.

6 A Zig-Zag path? The British government and navy averred that the Belgrano was pursuing a zig-zag path to avoid pursuers – and the Wiki site still does. “When torpedoed, we were pointing straight at the Argentine coast on a bearing we had been following for hours.” 4.4.83. If that ship had expected to be struck, as the Wiki site argues, then one would have expected such a course to be pursued: but, it didn’t.

To try and dispel the hallucinatory miasma cast by Friedman’s account, let’s quote from the diary of Narenda Sethia, on board the Conqueror, as published in The Observer. The Observer published this on 24 November 1984, then some further comments about this diary, and the trouble the Observer experienced upon publishing it, appeared in the Washington Post a month later, 23-24 December. Government agents were soon confiscating any copies of this diary they could find. The Post was not allowed to quote from the diary:

30th April, 1982: continuing passage to an area where the threats are from the Cruiser Belgrano – an ancient ex-US 2nd World War ship with no sonar or ASW capability, two Allen Summer Class destroyers – equally decrepit – and an oiler.’

Let’s now quote the original Gavshon and Rice position, from their 1984 book “The Sinking of the Belgrano’ which was generally endorsed by our Belgrano Enquiry, but dismissed in Freedman’s account:

By dawn about all surface units of Argentina’s high seas fleet were homeward bound, the Belgrano included, according to British as well as Argentine information. Exchanges between Lima and Buenos Aires and lima and Washington went on continuously. By the middle of the day Galtieri’s acceptance in principle of the Belaunde-Haig proposals was confirmed: the ratification by the junta was expected that night because a meeting had been set for 1900 (2200 GMT)

After the brief attempt to attack, when the wind didn’t blow, the fleet sailed homeward. Freedman’s account marginalizes the Peruvian negotiations and endorsed the government’s claim, that Northwood (the Navy’s control centre) and Checquers (the government’s decision-centre) only came to know of them three hours after the sinking. Therefore, let us quote from Cecil Parkinson, who was close to the Prime minister and on her ‘war cabinet’[10], on a Panorama TV program (19.4.84)

Cecil Parkinson MP: We knew that all sorts of people … wanted to see a peaceful solution … which the prime example was Presidente Belaunde

Panorama Presenter Emery: You knew that on Sunday 2 May?

Parkinson: We knew all the time that there were continuing processes

Then if we go back to the afternoon of 2nd of May, three hours before the Belgrano was sunk, President Belaunde on the phone to Costa Mendez in Argentina said this about their nearly-finished peace plan:

Belaunde: With the sole exception of this word ‘wishes’ which the UK has just insisted on, the rest is acceptable?

Costa Mendez: Correct’ (conversation 1200 Argentine time, that is 11 hours Falklands time,(p37, FAC Report)

‘The wishes of the islanders’ was a key phrase in their negotiations that everyone was struggling over.

The Real GCHQ Signals

By way of contrast with the fictional ‘intelligence’ Freedman claims to have been privy to – mysteriously kept secret for over twenty years – we conclude with an excerpt from an account by British journalist David Leigh, ‘Belgrano codes Cracked,’ The Observer 6.1.85. I suggest that our Belgrano Enquiry totally endorsed what he here wrote:

Four signals intercepted by Cheltenham CGHQ about the movement of the Argentine cruiser General Belgrano,[11] support the view that it posed no threat to the British Task Force off the Falklands when the order was given to sink it.

The four Argentine signals, intercepted by airborne monitors in the South Atlantic and relayed to Cheltenham for decoding, were: (1) An order to the Belgrano, late on 29 April 1982, to sail on patrol from the Argentine coast past the Falklands to a set point and then return. (2) An order on 1 May at 7.55 p.m. (London time) for two other elements of the Argentine fleet, the northern and central groups, to sail out and attack the British Task Force. (3) The countermanding of this order within four hours, at seven minutes past midnight. (4) An order confirming that the central and northern groups, were to be recalled to safe waters. This was in GCHQ’s hands soon after 5.19 a.m. on 2 May.

These signals show that the Belgrano was not engaged in the Argentine ‘pincer movement’ about which Navy chiefs claimed to have received intelligence. They also show that even the ‘pincer movement,’ involving the two northern groups, had been called off by dawn on Sunday, 2 May, the day War Cabinet members met at Chequers and accepted the urgent recommendation of Admiral Lewin, Chief of Defence Staff, that the Belgrano be sunk.

The GCHQ disclosures, reported last week and confirmed by The Observer, make clear for the first time why London’s order to sink the Belgrano was so puzzling that it had to be sent three times to the British submarine Conqueror.

Here is Sir Lawrence Freedman’s map, which well shows how very far away due North was the Vincente de Mayo. Remember, that circle is four hundred miles wide. Is anyone really going to say this looks like a ‘pincer movement’?

Conclusion

Let us hope that the 30-year release of official secrets casts some light upon the hardly-credible ‘new’ intelligence, on which Sir Lawrence has based his magnum opus. Clearly, GCHQ needs to be asked, why it kept this startling bit of ‘intelligence’ to itself for twenty years. If it can’t answer, Lawrence Freedman should be stripped of his knighthood. One could make a similar comment upon the new book ‘The Silent Witness’ by Major David Thorpe, 2011, which likewise claims to have startling hitherto-unheard of instructions about a Belgrano order to move inside the TEZ and attack the Task Force (yawn). No, in case you are wondering, the Thorpe newly-revealed intel is not compatible with the Freedman intel, they have different co-ordinates inside the TEZ. By way of trying to discourage any further amazing-but-fictional intel revelations, as the 30th anniversary draws nigh, let’s just say that any such intercepted GCHQ messages would have to have been put into the ‘Crown Jewels’ document, the dossier of state-secrets about the Belgrano, which were scrutinized by both Ian Mikado and Clive Ponting[12]. Both of these were present at our Belgrano Enquiry, (See here and here ) to guide it in reaching the just conclusions which it did. Let the truth emerge, not fictionally-fabricated MOD-source retrospective constructs.

This whole story reinforces the journalist’s motto, ‘Never believe anything until it’s been officially denied’. In particular, Journalists need to refrain from believing a government yarn just because it’s prefaced by, ‘secret report reveals…’

[1] ‘Freedman was knighted for services to Blairism after drafting the Chicago speech of April 1999 that launched the doctrine of illegal interventionism on the world’: Richard Gott, New Statesman-web

[2] Freedman has the Argentine fleet ordered by General Allara to turn back just after midnight ‘back to their former positions’ (p.290). That is four hours later than Gavshon & Rice have the carrier and escorts turn to return home, at 8 pm local time. We used the latter in our Timeline.

[3] This could be clarified by examining the row which broke out between the Argentine junta which ordered the fleet home that morning, and the Air Force which contested the order. Quoting Dalyell: ‘We now know what the orders from Argentina to its ships were, not least because Admiral Inaya – the navy member of the junta – has been bitterly and publicly rebuked by the pilots of the Aviacon Naval, the Argentine equivalent of the Fleet Air arm, who showed courage and skill in the conflict, for his treachery in issuing orders. They were that the Belgrano, the Piedra Buena and the Hippolito Bouchard should return to their home port of Uschia, and that is precisely what they were doing, on a 280 degree course west-north-west towards the entrance of the straits of Magellan, when the Conqueror struck some 50 miles outside the exclusion zone. House of Commons 24.3.83, Thatcher’s Torpedo p41. NB Gavshon & Rice say it was 36 miles outside the TEZ when struck, p.111.

[4] Al Haig, Caveat Realism, Reagan and Foreign Policy, 1984

[5] After the Belgrano had sunk, which caused the real, killing war to start, America then provided the RAF with heat-seeking, supersonic, air-to-air sidewinder missiles – enabling the British victory.

[6] New Statesman: 18.7.05 ‘A new history of the Falklands war defends nearly every aspect of the Tory government’s handling of the crisis, including the decision to sink the Belgrano.’

[7] British link to the Lima peace-plan: Arias Stella was ‘in constant phone contact with …British [ambassador in Lima] Charles Wallace, whom I knew very well ..advising [him] of every step in our peace plan negotiations. Wallace, a conscientious man, gave me the clear impression that he was referring back to London all the time (Phone interview with Desmond Rice, Han ’84, FAC p38) Wallace’s phone calls were being received by Lord Hugh Thomas in London, who chaired Thatcher’s Policy Studies Group.

[8] On 30th April, the so-called Mandarins Committee had made a change in the Rules of Engagement, which allowed British forces to attack the Vincente de Mayo aircraft carrier, based upon the range of its weapons i.e. its aircraft. The Foreign Secretary Pym wrote a letter to Thatcher criticising this change in the ROE, being uneasy that it might scupper the ongoing peace negotiations, for which he had been sent to Washington.

[9] Interview with Narendra Sethia in Buenos Aires, September 2000, these being Bonzo’s opening words upon meeting Sethia who had been in the Conqueror submarine which torpedoed his ship: Guardian, ‘Hit by Two Torpedoes’ 18.10.00. See also Gavshon & Rice, ‘Hector Bonzo has rejected the British claim that the attack was legitimate’ p111.

[10] FAC Report 1985 p.38, (does not give date of Panorama program)/

[11] Tam Dalyell, House of Commons 24.3.83: ‘I believe that Britain had cracked the not very sophisticated codes by which admirals in Argentina communicated with ships at sea, and on May 1 and 2, knew precisely what were the orders to the Belgrano and her escorts, the Piedra Buena and the Hippolito Bouchard’. Also, ‘I am told that for hours there had been no imposition of radio silence between the Belgrano and her escorts before the sinking as they imagined they were going home and peace was breaking out.’ (Thatcher’s Torpedo 1983 p37, 39)

[12] Clive Ponting said he was not allowed to view official telegrams in the ‘Crown Jewels’ dossier sent to and from America ‘if they exist’ before the Belgrano was sunk, but only after.

“The story coming out from our 1985 Belgrano Enquiry had been, that in the early morning of 2nd May 1982 the Argentine fleet turned round and headed for home because of the developing Peruvian peace plan, which the Argentine General Galtieri was accepting. ”

Don’t you think that this conclusion is strange as the Commander of the Belgrano has so clearly stated that his orders were to attack the British fleet?

Not that the Peruvian peace proposal was viable. It was never likely to be accepted.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/124713110/Falklands-War-Countdown-Conflict-1982

@Roger Lorton – Quite. The funniest thing is how this ‘inquiry’ (which in reality was nothing bu a self-constituted kangaroo court) twists Bonzo’s statements to suit their needs:

1) The ‘political crime’ that Hector Bonzo was referring to is unclear, Narendra Sethia (an officer on HMS Conqueror at the time) was the person who heard it and this is how he described it:

“The atmosphere was tense, and while I understood snippets of their exchange, much of it eluded me. Bonzo then turned to me and spoke in Spanish. He told me that, in his view, the sinking of the Belgrano had been “politically criminal”. I nodded and told him that I agreed with him and I felt that he hesitated at that, as if to take another, closer look at me. ”

Is Sethia admitting to a “political crime” here? Or is he merely saying that the politics which surrounded the war in general (which would include the Junta) were criminal? He later says that he did not regret sinking the ship, so it would appear to be the later. At the very least, this is not a specific statement that he regarded the sinking as a war crime. Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2000/oct/18/argentina.falklands

2) ‘Heading home’ Came from the same discussion between Sethia and Bonzo. Here’s how he describes it:

“I asked Coco if it was true that the Belgrano had been steaming home to Argentina and he said that, yes, this was true. In Captain Bonzo’s book, “Los 1,093 Tripulantes” (The 1,093 crew) Bonzo had suggested that he might, at a later stage, have changed course to the east, back towards the Falkland Islands, but both Coco and Barcena told me that they had been heading west, heading home.”

So basically Sethia actually undermines the idea that the Belgrano was heading home in the very statement you’re relying on, but you don’t acknowledge it. This is the very escence of quoting in bad faith. Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2000/oct/18/argentina.falklands

3) A statement from 1983, whilst the Junta was still in power. He later said:

“It was an act of war. The acts of those who are at war, like the submarine’s attack, are not a crime … The crime is the war. We were on the front line and suffered the consequences. On April 30, we were authorised to open fire, and if the submarine had surfaced in front of me I would have opened fire with all our 15 guns until it sank.”

Seems he’s disavowed the idea that they were no threat to the British fleet there;. Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/blog/2007/may/02/belgranoannive

4) A statement about the illogicality of the exclusion zone – but does this mean that he seriously believed that the ship was not in danger? It shows nothing of the kind – see the above quote: they were authorised to open fire, they believed themselves to be on the front lines. Admiral Molina Pico has stated that they were all aware that to leave the exclusion zone was not to leave the zone of combat. Source: http://www.lanacion.com.ar/700676-cartas-de-lectores

5) A rather old statement pooh-poohing the idea of a pincer movement without explicitly denying it. Since then we’ve heard from Admiral Pico Molina an explicit statement that the Belgrano was part of a co-ordinated operation that was holding off ready to strike. That the pincers were 400 miles apart is immaterial – the Vientinco De Mayo had aircraft that could cover that distance. Source: http://www.lanacion.com.ar/700676-cartas-de-lectores

6) Again, a Junta-era statement, and again, one which does nothing to actually disprove the idea that the Belgrano was zig-zagging. It is quite possible that the Belgrano both zig-zagged and held a course towards Argentina – all this required is that the zig-zagging was shallow. See the quotation above for evidence that Bonzo knew his ship was at risk – under those circumstances, zig-zagging would have been very logical.

The crazy thing about this is that you acknowledge that the Argentine navy did attempt to attack (“After the brief attempt to attack, when the wind didn’t blow, the fleet sailed homeward”), but then act as if this meant nothing. In reality it means everything. It is silly to dismiss the idea of a co-ordinated attack whilst simultaneously admitting that one was attempted. It is silly to dismiss the idea that the Belgrano was a threat whilst ocnceding that it attempted an attack. It is silly to continue with the idea that the Peruvian peace plan was viable whilst conceding that the Argentines were attempting to destroy our fleet at the same time.

This argument is not in good faith, but a botched job of trying to trim the facts to fit your pre-conceived verdict.